![]()

![]()

In the Artist's Studio with Thomas Paquette and Mary Soliwoda

February, 2010

interview by Mary Soliwoda

source

|

THOMAS PAQUETTE— An Interview by Mary Soliwoda

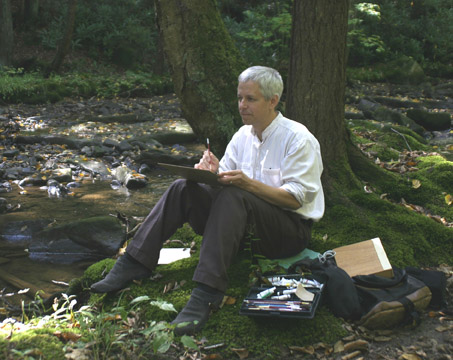

Whether it's a tiny, postcard sized gouache, a 14" x 16" oil on hemp, or a wall-sized installation at a college, Thomas Paquette brings to his work the hand of a gifted artist and the spirit of a true poet. In the following recent interview you'll come to better understand what drives that spirit, keeps it strong, and keeps it evolving. A native of Minneapolis, Paquette has lived for a time in southern Illinois, Miami, Florida, and the state of Maine. Since 2001 he has resided in northwestern Pennsylvania, where his creative powers are fed by the intrinsic depth of beauty found in the nearby Allegheny National Forest. His residencies in Italy, Greece, England and Wales have only enhanced his work, drawing on nuances that might otherwise have gone untapped. Enjoy the interview, but look at Thomas Paquette's work. Look into the art, and be drawn into the world of subtle drama and dramatic beauty he finds in ordinary places. All of the light, darkness and shadow - as well as the insinuation of hue and tone - nature and life are expressed. MS - At what point in your life did you know that you are an artist? TP - I believe that we are all born potential artists. Most of us make art until we think we are better suited to other things. I just never wanted to stop. I loved drawing and painting and was saddened when peers I thought were good gave it up. Until I went to college, I seemed to be the last lonely man standing. I had an epiphany of sorts when I was twelve about the direction I felt my life should take. A dog ripped into my right hand and in my fear I thought it would have to be amputated. The only thought I had after that - and it really shook me to the core - was how was I going to be an artist now? After that moment I valued my passion for art in a new way, and tried to make sure that nothing would prevent me from being an artist. MS - What most inspires your work? Sights, sounds, nature, music, people, etc.? TP - Most simply, I get excited to see colors do new things. It could be on a canvas or in a scrap of red light filtering through the trees and coloring a solitary tree trunk. As subject matter, I find the natural world full of endless variations not only in form but also in color. Too, I am inspired by other art. The subtlety of the Renaissance masters, the wafting colors of Bonnard, the delicious mayhem of Kiefer. I am the guy at museum whose nose practically touches the paintings, unable to keep my distance. I would probably eat the stuff right off the canvas if it weren't toxic. MS - What part of the creative process do you find most exciting or engaging? TP - I think the part that most excites and engages me is just before a painting is done. All the great and small color shifts, all the balanced shapes and configurations of the painting, everything comes to a kind of crescendo at that point. And since I never actually have precise plans for a painting - only inklings of direction as I move from interest to interest across the canvas - it is somewhat mesmerizing as I see it begin to coalesce into a whole in the end. MS - How do you make the choice of the manner and the materials you use in your work? TP - I like to shake things up as often as possible to avoid habit and ossification. Sometimes paintings are thick with impasto, other times just a thin film across the canvas, sometimes bright, sometimes dimly glowing. It is often a matter of choice in materials and tools. I have perhaps over a thousand paint brushes in my studio, from 00 sables to 4 inch hardware brushes, all ready to change my preconceptions about painting when I feel trapped by a method, material, or tool. The enemy of creativity is predictability. MS - Do you render sketches or an under painting before you begin a project? TP - My paintings begin in all sorts of different ways, but one thing I never do is draw with any detail on the canvas. I learned not to do that a long time ago. A painting evolves for me and can hardly be prescribed. As an example, one medium-sized painting began with some small trees in the median in a highway. Within a year - and after many shifting compositional changes - it became a broad marsh. The painting took a serious turn (literally, from a horizontal to a vertical) a couple years later when it became an northern river during spring ice out. If I still had the painting in my possession, I might well be tempted to change some little thing (this is how it always begins, innocently: just a little color change here, a little drawing change there), that might completely alter it again into who-knows-what. So drawing details at the start would only add more insanity than is wise. MS - You’ve done everything from postcard sized gouaches that are exquisite to monumental sized commissions. Emotionally, what is the difference in your approach to works which vary so widely in size? TP - I am not sure there is an emotional difference in my approach to such varying scales. In all works I seek a certain point at which the painting seems to come alive in its own peculiar way. The biggest difference is that the large ones tend to take far longer to realize, and so I tend to contemplate the creative options more before I commit them, to make each application of paint as meaningful as possible. It takes a more deliberate intensity to accomplish, whereas small works are more malleable in some ways, and prone to more abandon. MS - Discuss which part of the creative process you find most stressful. TP - All of it is stressful if you are doing it right. MS - I’ve read that you sometimes use photography as a touchstone to a memory of a place or scene. Tell us about any special equipment or lenses you may use. TP - Other than little gouaches, I rarely work on site anymore as it has become so counterproductive. Even the gouaches begun on site are usually completed after some revamping in the studio. Temperamentally I am not a plein air painter. My works develop over long periods of time, especially the larger ones which typically take months. So photography has been a useful tool for bringing the subject back before my eyes. I started by using black and white photographs I’ve shot, so that I would be forced to invent the color through memory. Later, when I felt unfazed by the lure of camera color, I used slides - typically never seen projected - as tiny luminous flashbacks to the subject matter I was trying to evoke. I could go back there instantly by holding the slide up to the window for a few seconds, and would do this infrequently, only when I was stuck or needed to find a new element to introduce to a composition. Observing the elements of a photograph, like observing the elements of nature, can provide new insight to improving a composition, while still remaining true to the subject. Being able to refer to the subject keeps a painter from relying too heavily on imagination, which surely becomes manneristic if it is not fed new information from life. The opposite problem to avoid of course is relying too heavily on the dictates of the photograph. I use no special photographic equipment as it is merely a means to an end, simply an instantaneous if somewhat over complete sketch. MS - Have you completed works that you find difficult to part with, and why? TP - Ha. That would be true of most of my paintings. Primarily because they can always hold more paint, and I am always game for changing them. But there are also some other paintings I like to keep around for a while because they represent a direction - though interesting - that I may decide to forego. Or because they hold a lesson I am not sure I have completely absorbed yet, and need to contemplate. MS - Do you take "a break", or days away from a work while it is in process? TP - Always. It is essential to do this, and is the reason I have perhaps a dozen paintings in play at any time. Regarding the length of a break, it may be enough to refresh my sight after two minutes or it may be five years. I just recently "finished" a painting I first thought I finished twenty years ago which, prior to this last iteration, has been hung in museums and been reproduced full-page in a magazine. MS - What do you for recreation and how does it complement your work? TP - I am not sure it could be called "recreation" but I love to travel. Travel transforms routines into contemplative, sometimes frenetic, adventures. Just waking up in the morning becomes an event. Coffee just tastes better in Italy, even if it is instant. When a painting session is at its best, this is the sort of mentality I have. Fresh new eyes. Travel hones this frame of mind, this alertness. I also find that taking extremely slow walks in my woods and noticing the smallest detail of the world is very exciting to me. A sort of walking Zen. An insect, a flower, a chunk of decaying wood, or the riffle of a breeze can erase all thought and focus my mind more sharply than I thought possible. This is the same attention I use when I am in the midst of painting, even though it is not my subject matter precisely. MS - How do you manage to sustain your interest in a project when it "isn't working"? TP - I don't. Boring work will make boring art, I think. I stop and see if it isn't simply my own attitude that isn't working. If that isn't the problem, no matter how "complete" it is, I set out to ruin the painting beyond recognition - at least the area I perceive isn't working - and start fresh on the issue. There is a lot of creative force unleashed in destruction. Trying to perfect something that is ungainly - particularly something that you have labored long at developing - is like trying to talk a chair into walking. MS - When do you know that a work is finished? TP - As a painter more poetic than me put it, "A painting is never done; it just stops in interesting places." (Some have attributed this to Matisse, but I believe it was someone else.) MS - In what way would you like to see your work evolve from here? TP - I have some ideas about directions my work may take. But because I don't like to follow plans, orders, or recipes, these things are best left inchoate if they are ever to come to pass. There is a Zen/Tao sentiment I always keep in my heart: Without a path, the way is perfect. Of course this doesn't mean not moving forward, but it does warn against laying out artificial goals that may distract from a more significant purpose. MS - Discuss how you create a painting—the process, the materials, the worktable, your timetable, etc. TP - My palette is a large glass plate on one rolling table. On another rolling table I have about 50 large tubes of different colors laid out spectrally so I can find them easily. I am shockingly orderly sometimes, but mostly it is so I don't poison myself or struggle too long looking for a certain red. I use a large oak easel with a "speed gear" on it, which isn't so fast after all. I lay out blobs of color on my palette spectrally too, with a variety of warm and cools in each hue. I will pre-mix tones only after I am well into the painting. At first it is very thin washes, just to establish some guidelines. After I have established what subject I will paint, the first step is to decide whether it is best expressed in a large work or on smaller dimensions, or whether I should work it on a couple different scales. Another decision is whether to paint on coarse or smooth linen, a wood panel, or even a troublesome canvas that has already been painted on. I then cover the canvas in colors that sometimes do, but more often do not, approximate the finished colors. And sometimes I cover the canvas with arbitrary paint just to give me something to "work against". Another initial approach I sometimes take is to conceive the composition as a big loose drawing using just one color. As unruly as my process is up to that point, I can't even tell you what happens next because it is game with no rules, except one: to make something to look at that is as interesting as possible, perhaps even beautiful. MS - Discuss your use of the types and varieties of brushes and the various mediums and how they impact the intimacy of your finished work. TP - I use anything from a very thin sable to a wide bristle brush in the same painting, at any stage therein. I try to be counterintuitive, but sometimes rationality wins. Although I used to use lots of mediums and experiment with different formulas, I use very little now, in part due to solvent toxicity and my reactions to them. And I love the varying textures that can be pulled out of oil paint, so sometimes using a thinner is a moot issue. Foremost is my intention of creating something that, like the micro and macro ecologies of a forest, functions on all sorts of levels, so that viewing it from three inches away is as gratifying as seeing it across a room. MS - How large is your studio, and what do you like most about the physical space? TP - My studio is about 1200 square feet with north windows predominating. There is only one small set of windows to the south that I can block off when the sun shines and there is a big bubble of a skylight (8×8 feet) right over my painting area. Sometimes it feels like I am painting outside. The correct light for me is crucial and my studio was built to accommodate that. I only paint under natural light. In graduate school I painted under artificial light, but I discovered that the limited spectrum of artificial lights makes for unpredictable colors in the morning. Even with top-end industrial color-matching specialty lamps, most of the paintings I worked on under artificial lights are the next morning exactly as unsatisfactory as you might expect such a one-night stand to be, and had to be reworked in the full light of day. It was as though a drunk wearing sunglasses had worked on my painting. MS - Do you prefer to work in the quiet, or with music or other sounds in the air? TP - I like to listen to music, and am very particular about it. The music must have a sense of adventure and invention in its core. As much as I love Beethoven and all his powerful themes and invention, music with a raw edge and force - and fine skills driving it - seems to bring out the best energy in my work. Fortunately my nearest neighbors are several hundred yards away and don't need to share my enthusiasms. MS - Discuss your more recent works that are favorites, and why. TP - "Dance of Clouds" is a recent favorite. I wanted to depict these crazy little clouds - easily ignored in daily life - that seemed to be involved in some kind of slow dance to an invisible, atmospheric music. They reminded me in some odd way of Matisse's "La Danse". My depiction would include a great deal of blue sky, but I was able to temper its presence with small inclusions of under painting, which could have been too-easily lost in the process. It was kind of a hold-your-breath couple days as I repainted the sky a couple times. Another painting that I want to mention is "To Colmars". Although it took far longer to paint than it seemed it should have (it is, after all, simply a snow-glazed mountain emerging through veils of fog, mist and cloud), ultimately this gray little painting has a plethora of color emerging in the distance, where one least expects to find - by the conventions of art anyway - the most intense colors. And that sort of upset is very satisfying to me.

"Dance of Clouds" 36" x 46" MS - What would you like your audience to take away from viewing your works? TP - My hope is that my audience will catch the excitement I have for color. And too, I hope it they share my enthusiasm for the vibrant world of nature and our place in it. The paintings tend to draw from me a sort of awe regarding perception and existence, and if others connect with that in their own lives, so much the better. MS - What present or future work would you like to discuss? TP - I don’t like to discuss what I am working on. Energy seems to drain from the impetus when it is dealt with symbolically and hypothetically in discussion. For me, the best discussion of current work will be seen in the paint itself when it is done. The painting will materialize my thoughts about color and for. By example, I witness great inspiring diatribes by Bonnard or van Gogh when I see what they have done on their canvases, almost as though the works are still being created. That is the sort of discussion I want to have, between my finished canvas and the viewers’ eyes, an artwork in the making. MS - Is there any specific contemporary or historical artist whose work you admire or try to evoke in your work? TP - There are scores of historical and contemporary artists I admire and whose works speak to me. Naming just a dozen would skew the balance unfairly! I suppose among historical painters though, Pierre Bonnard and Andre Derain are near the top. Not that their works should resemble mine. I should add though that I actively try to shove all artists (especially contemporary ones) out of my mind when I am creating. I find it distracting to be conscious of another artist's choices while I am trying to invent something new! If Monet (metaphorically) comes into my studio, I will acknowledge his presence, invite him to tea, and then give him a swift boot so I can get back to my own work. I doubt I would be much kinder to Bonnard. MS - What words of encouragement or wisdom would you like to share with amateur and/or emerging artists? TP - If your life is an artwork, how will you shape it? Your greatest asset is your passion. Find what really interests you and pursue that without looking for approval or remuneration. Your passionate involvement is by itself the most valuable reward in any endeavor; be careful not to trade that for a steady but dulling income. If you care to be an artist, you must learn to survive simply so you can do your next artwork. |

To inquire about paintings: paquette.studio@gmail.com